JSON has become a common data format for modern applications, and as a result, many teams evaluate whether a single database can serve both relational and document-style workloads. PostgreSQL’s JSONB support and MongoDB’s BSON document model often appear comparable at a glance, leading to the assumption that they can be used interchangeably.

However, while both systems expose similar query and indexing capabilities, their internal storage models and execution paths differ in important ways. These differences are not immediately visible through APIs or simple benchmarks, but they begin to surface under realistic workloads involving frequent updates, indexing, and concurrency.

This article explores those differences through a series of controlled experiments, focusing on how each database stores JSON-like data, how common operations are executed, and how these design choices influence performance and resource utilization over time.

What is JSONB?

JSONB is a PostgreSQL data type that enables applications to store JSON-like objects natively within a relational table, alongside traditional columns. Internally, JSONB stores data in a binary format that enables efficient parsing, indexing, and querying compared to plain JSON text. This capability has made PostgreSQL an attractive option for teams looking to work with semistructured data without moving away from a relational database.

However, an important question arises when JSONB is used beyond simple storage and querying: How does PostgreSQL actually process JSONB internally? We can separate this into two more specific questions: Does PostgreSQL flatten JSONB documents into individual values during execution, or does it operate on the document as a whole? And if the document is not flattened, what are the performance implications of this design under real application workloads?

These questions become especially relevant when PostgreSQL is evaluated as part of a modernization strategy, often driven by developer familiarity and the convenience of using JSONB as a substitute for a document database. While JSONB offers flexibility and expressive query capabilities, it is not immediately clear whether this flexibility translates into equivalent performance characteristics when compared to systems designed natively around document storage.

This article explores these questions by examining how PostgreSQL stores and processes JSONB, and how those internal behaviors influence performance under common workloads. The goal is not to compare features but to understand the practical consequences of using JSONB as a foundational data model in modern applications.

What is BSON?

BSON, or binary JSON, is more than a serialization format used for storing data on disk. It is a foundational representation that MongoDB’s query engine, update operators, and storage engine are designed around. While BSON appears similar to JSON at a superficial level, its binary structure enables users to address fields and arrays to be addressed by position rather than treat them as single serialized object.

MongoDB’s default storage engine, WiredTiger, works closely with this representation by managing data at a fine-grained binary level. Each field in a BSON document is stored with explicit type and length information, enabling the engine to locate and modify specific fields efficiently. This design enables MongoDB to apply update operations—such as $set—directly to targeted fields without requiring the entire document to be read, reconstructed, and rewritten in memory.

As a result, updates can be performed with significantly lower memory and I/O amplification compared to systems that treat documents as monolithic values. The impact of this design becomes especially visible under update-heavy workloads, which this document explores through a proof of concept.

Proof of concept: An update-heavy workload

To understand how PostgreSQL JSONB and MongoDB BSON behave under sustained update pressure, I designed a controlled load test that simulates a common application scenario: frequent updates to existing JSON documents.

In this scenario, the application continuously updates documents stored as JSONB in PostgreSQL and BSON in MongoDB. The objective is to observe how each database handles update-only workloads over an extended period, particularly with respect to latency, throughput, and system stability.

The same logical data model and update pattern were used across both systems. The tests were executed with the following configuration:

Test configuration

Concurrency: 256 concurrent workers

Test duration: 30 minutes

Workload type: Update-only

Total existing documents: ~13 million

PostgreSQL environment

Deployment: AWS RDS PostgreSQL

Instance type: m5.xlarge - Cannot Auto-scale(4 vCPUs, 16 GB RAM)

Connection pool size: 200

Storage format: JSONB

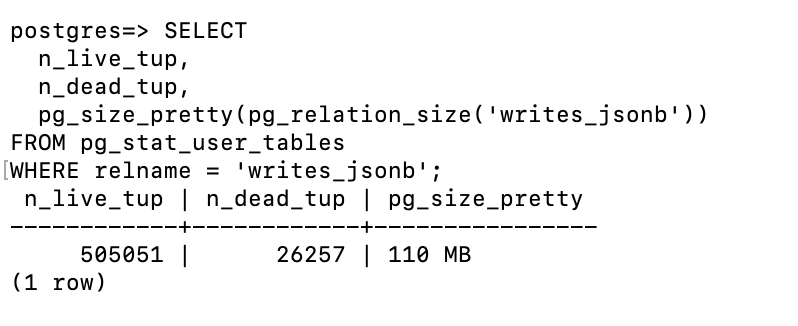

Existing heap-only tuple (HOT) size : 106 MB

MongoDB environment

Deployment: MongoDB Atlas

Cluster tier: M40 (4vCPU , 16 GB RAM) - Auto Scale Up M50 (8vCPU , 32 GB RAM)

Connection pool size: 2,000

Storage format: BSON

Fragmentation : Nil

Document characteristics

Average document size (PostgreSQL JSONB): ~163 bytes

Average document size (MongoDB BSON): ~90 bytes

Number of Indexes : 1 (User_id)

Overarching configuration

I intentionally chose this configuration to reflect realistic production settings rather than synthetic microbenchmarks. The connection pool sizes align with best practices for each database’s connection model, and the document sizes represent typical application payloads with nested fields.

The following sections analyze the observed behavior of both systems under this sustained update workload and highlight the architectural factors that influence their performance characteristics.

Results and Observations

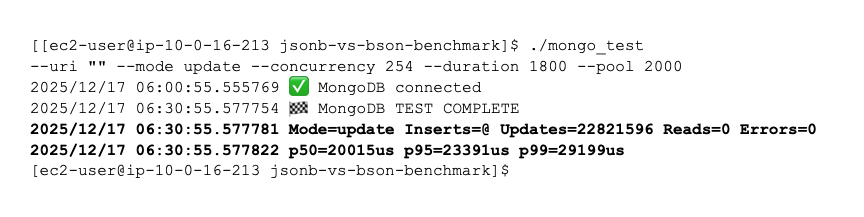

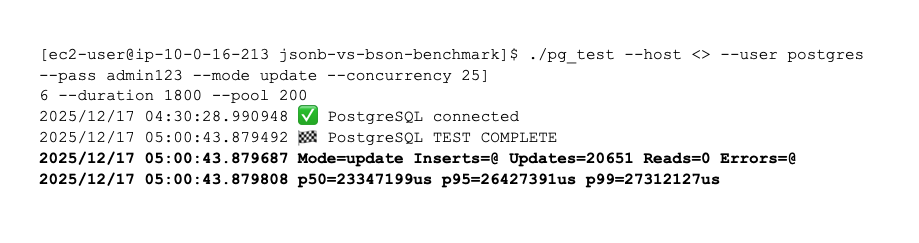

Throughput collapse under JSONB updates: MongoDB sustained ~22.8 million updates over 30 minutes (~12.7K updates/sec). PostgreSQL completed only ~20.6K updates total (~11 updates/sec). This is a ~1,100× difference in update throughput under identical client concurrency. This gap widened over time, indicating that PostgreSQL’s performance degraded as the test progressed, rather than stabilizing.

Figure 1. MongoDB test result.

Figure 2. PostgreSQL test result.

Tail-latency divergence: MongoDB’s p99 latency remained under 300 ms, even after 30 minutes of sustained updates. PostgreSQL’s p99 latency reached ~27 seconds, indicating severe queueing and resource contention. The PostgreSQL latency profile shows a system that is no longer keeping up with the incoming update rate.

Impact of Update Semantics: MongoDB: Updates were applied using $set on a single nested field (profile.score), enabling in-place modification without rewriting the full document.

PostgreSQL: In PostgreSQL, each update to a JSONB document resulted in the entire JSONB value being rewritten and a new row version being created under multiversion concurrency control (MVCC). Even when only a single nested field was modified, the previous row version became obsolete, leading to rapid dead-tuple accumulation. This behavior increases write-ahead logging (WAL) generation, triggers more frequent autovacuum activity, and amplifies both memory and I/O usage, especially under sustained update-heavy workloads.

Correlating CPU utilization with p99 latency

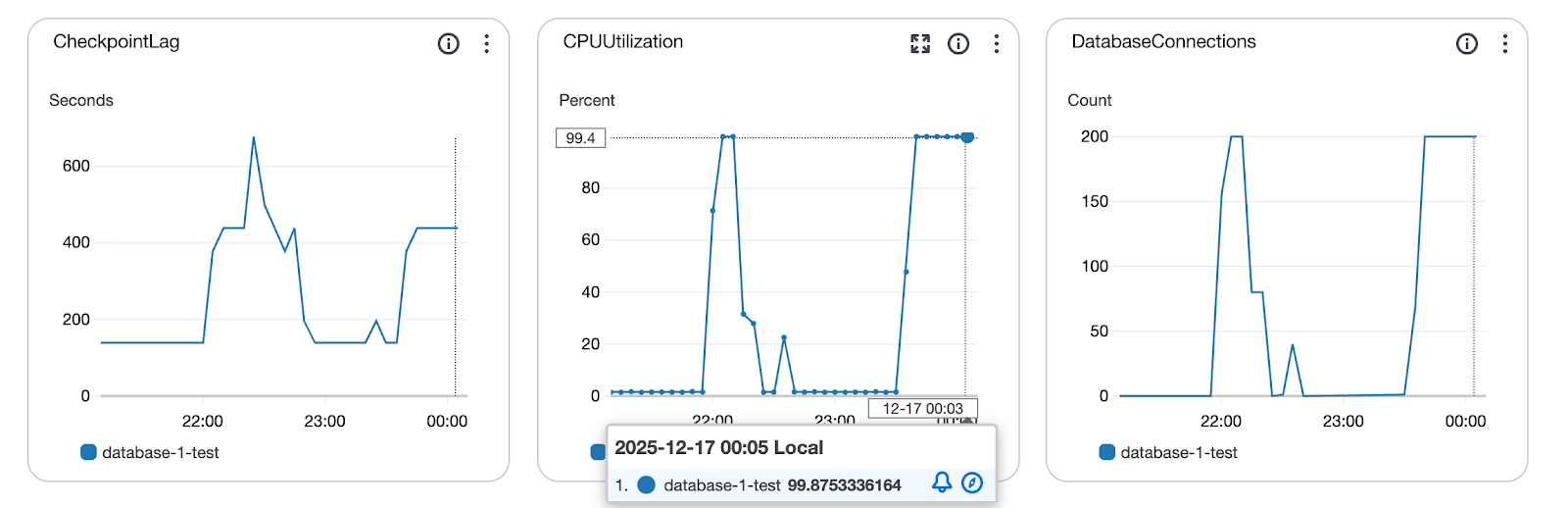

PostgreSQL analysis

Under the JSONB update-only workload, PostgreSQL repeatedly reached near-complete CPU saturation at approximately 99%–100%. Rather than improving performance, this saturation coincided with a sharp degradation in application behavior: p99 latency rose into the 20–27-second range, while throughput collapsed to roughly 10–15 updates per second.

This indicates that high CPU utilization does not translate into productive work; instead, CPU cycles are consumed by internal processing overhead, including full JSONB rewrites, MVCC row version creation, and the inability to consistently apply HOT updates. Because JSONB updates often change indexed or large values, HOT optimizations are frequently bypassed, leading to additional index updates, increased WAL generation, and rapid dead-tuple accumulation. The combined effect is increased queueing and progressively worse tail latency.

Figure 3. RDS CPU utilization.

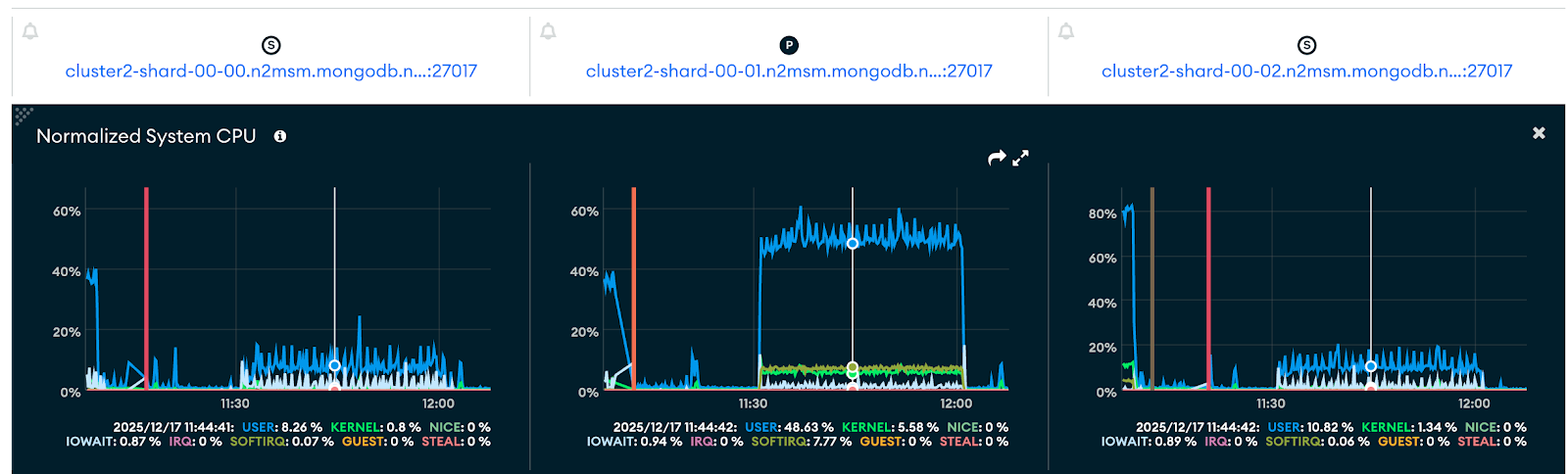

MongoDB analysis

Under the same update-only workload, MongoDB exhibited a markedly different behavior. CPU utilization remained moderate and stable throughout the test, while p99 latency stayed consistently subsecond at approximately 300 ms, even over a sustained 30-minute duration. Throughput remained steady with no signs of degradation, indicating that MongoDB was able to convert CPU cycles directly into completed update operations. As load increased, CPU usage scaled proportionally with useful work rather than internal overhead, keeping tail latency bounded.

This highlights a fundamental contrast between the two systems: In PostgreSQL, higher CPU utilization correlates with worsening p99 latency, whereas in MongoDB, higher CPU utilization correlates with higher throughput because update operations target specific fields using $set and BSON’s field-addressable layout, enabling the database to avoid full document reconstruction and unnecessary memory copying.

Figure 4. MongoDB Atlas CPU utilization.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that PostgreSQL JSONB and MongoDB BSON are fundamentally different in both design intent and execution behavior, despite their superficial similarity at the API level. While JSONB provides flexibility and convenience within a relational database, it remains constrained by PostgreSQL’s MVCC-based storage model, where updates to JSONB documents require full value rewrites and the creation of new row versions. Under sustained update-heavy workloads, this behavior leads to dead-tuple accumulation, increased WAL generation, autovacuum contention, and significant memory and I/O amplification, ultimately manifesting as severe tail-latency degradation.

Figure 5. Heap-only-tuple size increases.

MongoDB, by contrast, treats documents as first-class citizens through its BSON representation and update operators such as $set. By targeting specific fields rather than reconstructing entire documents, MongoDB is able to convert available CPU capacity directly into application progress. This field-addressable execution model enables MongoDB to sustain high update throughput with stable latency, even under prolonged load and high concurrency.

These findings highlight an important distinction for architects and developers evaluating modernization strategies. JSONB is well-suited for flexible schemas, occasional updates, and hybrid relational use cases, but it is not a drop-in replacement for a native document database when workloads involve frequent, fine-grained document mutations. In such scenarios, the architectural choices underlying BSON and MongoDB’s execution engine provide clear and measurable advantages.

Ultimately, the decision is not about feature parity but about alignment between workload characteristics and storage semantics. Understanding how data is stored, updated, and managed internally is critical to selecting the right database for modern, high-throughput applications.

Next Steps

If you would like to reproduce the benchmark results, follow the steps below to execute the load tests against PostgreSQL and MongoDB.

- Clone the repository from the URL: https://github.com/nhpjoshi/Assets2.git

- Go to the directory and use the linux/unix command to execute the following:

- Postgres load-test command: ./pg_test --host

--db postgres --user <> --pass <> --mode update --concurrency 256 --duration 1800 --pool 200 - MongoDB load-test command: ./mongo_test --uri "mongodb+srv://<>:<>@

" --mode update --concurrency 256 --duration 1800 --pool 2000

- Postgres load-test command: ./pg_test --host