MongoDB has supported distributed, multi-document transactions since 2019, enabling ACID, cross-shard transactions at snapshot isolation. In this post, we will dive into how the distributed transactions protocol works in MongoDB and discuss recent work we have done on formal modeling and verification to examine our transactions protocol in more depth.

This includes our work on the development of compositional TLA+ specifications for MongoDB’s transaction protocol, which enabled us to define and check its high-level isolation correctness guarantees. With these specifications, we were also able to formalize the interface boundary between the distributed transaction protocol and WiredTiger, the underlying key-value storage engine, enabling rigorous assurance of complex, cross-layer system interactions.

In addition to outlining how to use these specifications for checking protocol correctness, we also discuss a novel, quantitative approach to measuring permissiveness of a transaction protocol: a computable metric of how restrictive a protocol is in its implementation of a given isolation level. This is a new dimension to protocol analysis: not just a binary outcome of correct or incorrect, but an observation that a correct transactional protocol lives on a spectrum of efficiency.

This post also serves as a high-level companion to our recently published VLDB ’25 paper, Design and Modular Verification of Distributed Transactions in MongoDB, which presents a deeper technical exploration of these topics.

Distributed transactions in MongoDB

MongoDB implements a distributed, multi-document transaction protocol that provides snapshot isolation for transactions issued by clients using a general, interactive transactional interface. This is opposed to some other, more limited modern transactional systems that require upfront declaration of read and write operations. This enables users to program transactions using a familiar, programming-language-oriented API, executing transaction operations sequentially as standard statements in their application language.The distributed transactions protocol in MongoDB uses causally consistent timestamps across a sharded cluster for managing ordering and visibility between transactions, and it executes a two-phase commit-based protocol for ensuring atomic commit across shards. We developed distributed transactions in MongoDB incrementally, across three versions, building up from single-node transactions (v3.2), to single replica set transactions (v4.0), to full sharded cluster transactions (v4.2). So, the distributed transactions protocol in MongoDB can be understood as layered on top of a single-node, multiversion, transactional key-value storage engine, WiredTiger. This storage engine implements local, snapshot-isolated key-value storage, along with additional API methods for integrating with the two-phase distributed transaction commit protocol.

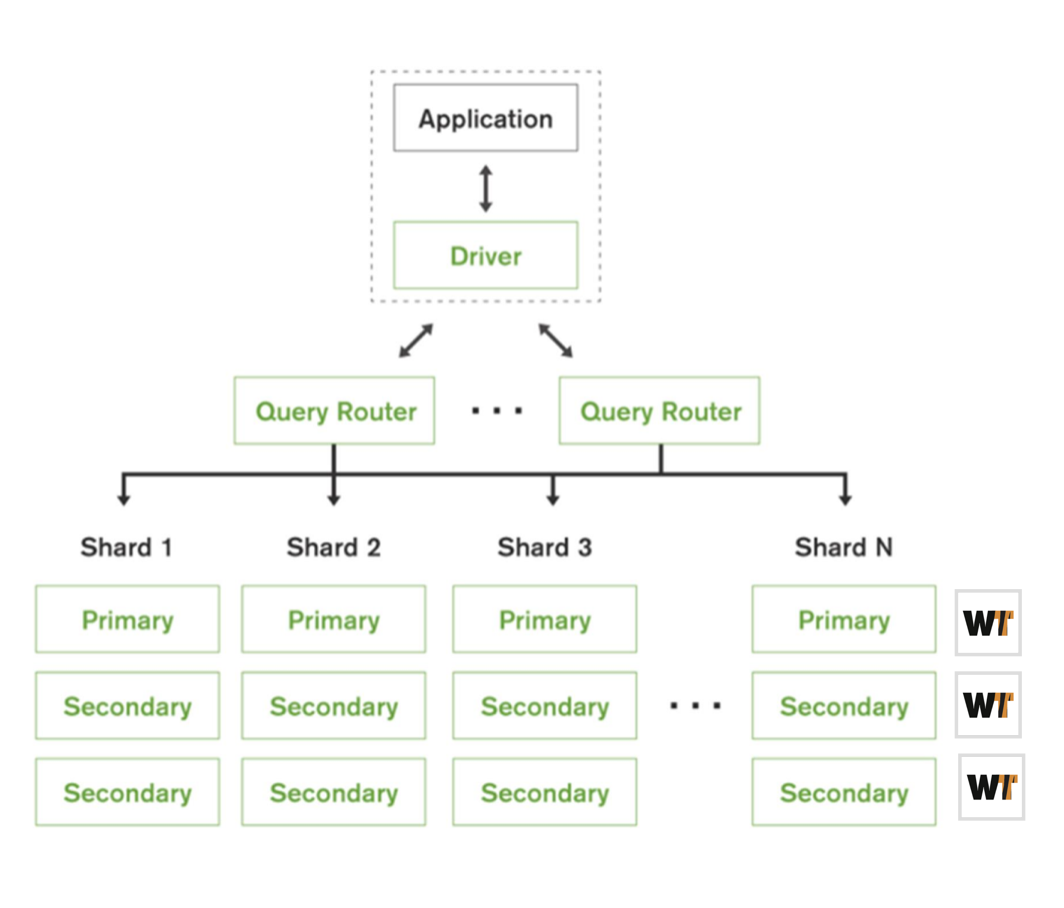

Figure 1. Basic sharded architecture of MongoDB.

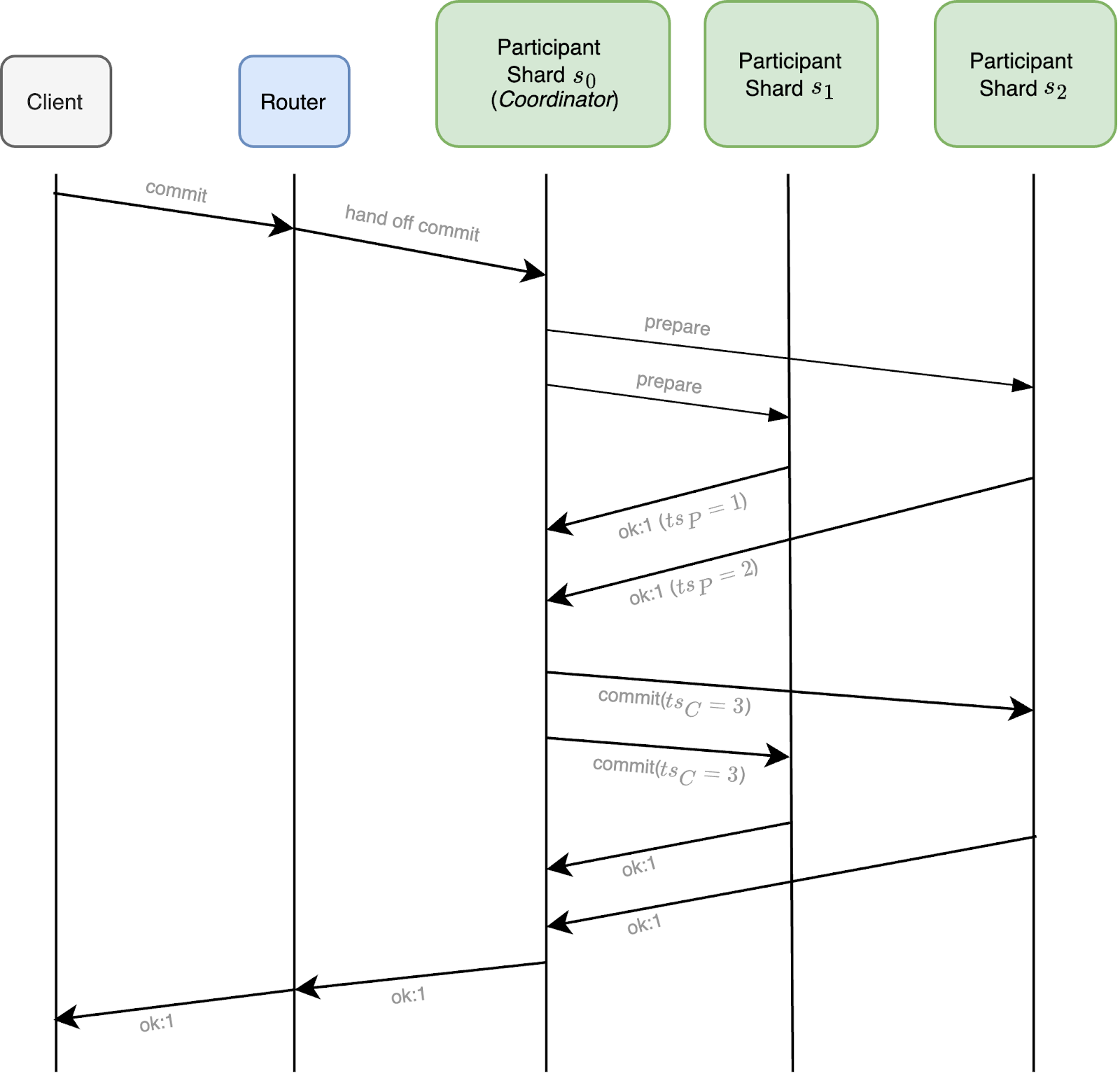

Upon receiving successful prepareTransaction responses from all participant shards, the coordinator then computes a commit timestamp for the transaction, chosen as a timestamp greater than or equal to all received prepared timestamps. It then proceeds by sending out a commitTransaction command to all participant shards, along with this commit timestamp, and each shard will then execute the transaction commit locally, making that transaction’s writes visible at the given commit timestamp within the storage engine.

Clients interact with a sharded cluster through mongos, stateless router nodes that route operations to the appropriate shards based on the data being touched by a query. Upon the start of a transaction, the associated router will assign a global read timestamp to the transaction, and then continues servicing the transaction by dispatching ongoing transaction operations to the appropriate shards, based on which keys the transaction operations read or write.

If the transaction completes successfully without encountering aborts due to write conflicts or other internal errors, it proceeds by initiating a variant of two-phase commit (2PC). The router begins this process by handing off the 2PC process to a coordinator shard to ensure durability of the 2PC lifecycle data during its execution. The 2PC process executed by the coordinator then begins by sending prepareTransaction messages to all shard participants, which executes a prepare phase on that shard. This phase consists of selecting a prepare timestamp at that shard and making the writes of that transaction durable by persisting and majority committing a prepare log entry in that shard’s replica set.

Figure 2. Basic commit flow of multi-shard distributed transaction, with associated timestamps.

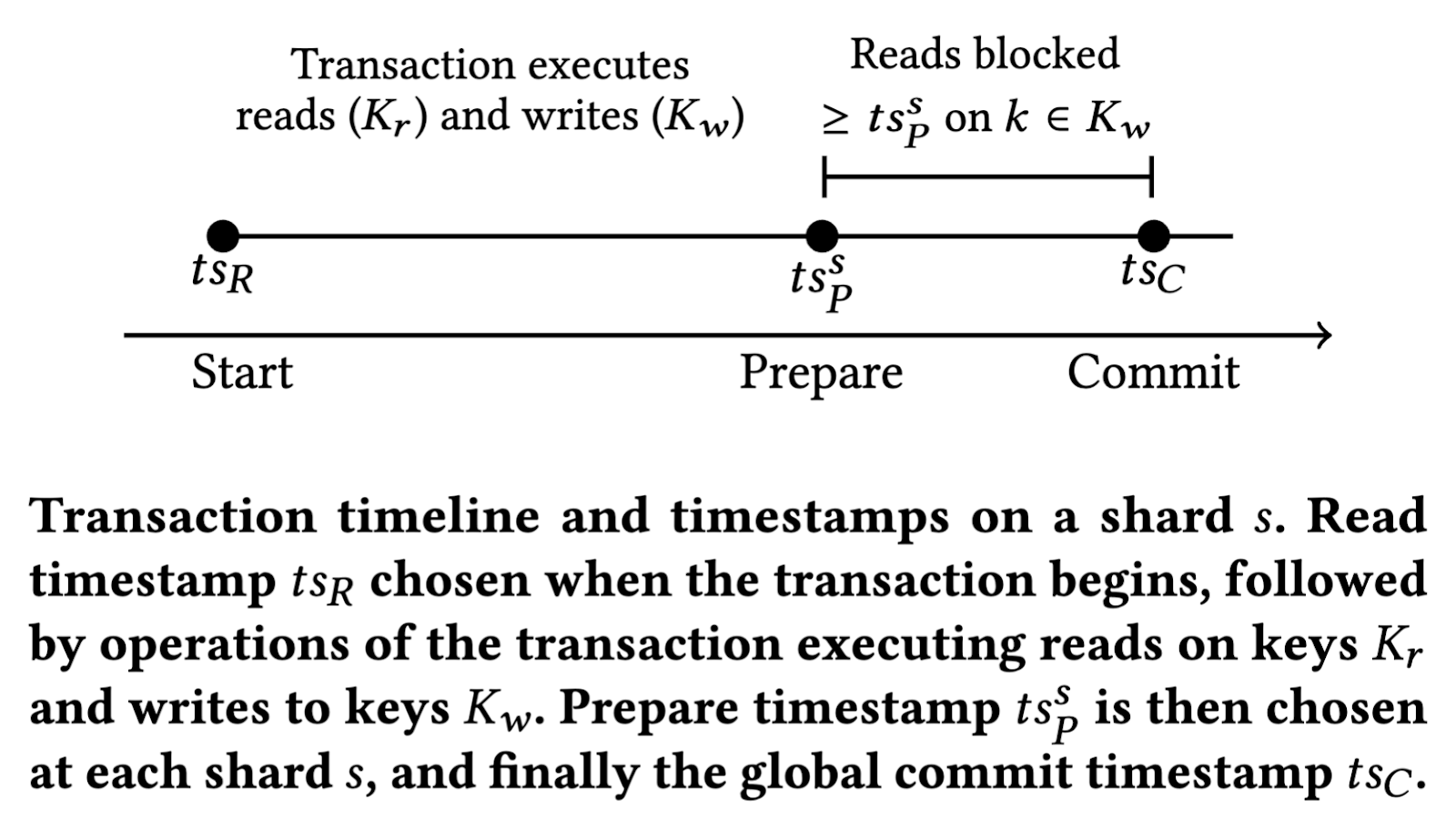

Note that when a shard enters the prepare phase for a transaction, it also marks the keys for that transaction in a prepared state at the storage engine layer. This enforces a behavior that any read at a timestamp greater than or equal to this prepared timestamp will block against this key, since the commit timestamp of that transaction is not yet known, so we must block before knowing whether to read before or after that transaction’s timestamp.

Figure 3. Timestamp blocking behavior for prepared transactions.

Note also that standard write-conflict checking behavior of snapshot isolation applies during transaction execution at each shard as well. That is, if two concurrent transactions try to update the same key at the same shard, one of them will be forced to abort.

There are also some additional optimizations around when 2PC can be bypassed—for example, for read-only transactions or for transactions that only write to a single shard—but the above describes the general flow of distributed transactions in a MongoDB sharded cluster.

Specifications for our protocol

Writing a formal specification of the distributed transactions protocol is the first step toward gaining confidence in the protocol’s precise correctness and isolation properties, and it also enables several other protocol analysis and verification tasks, as we discuss below.

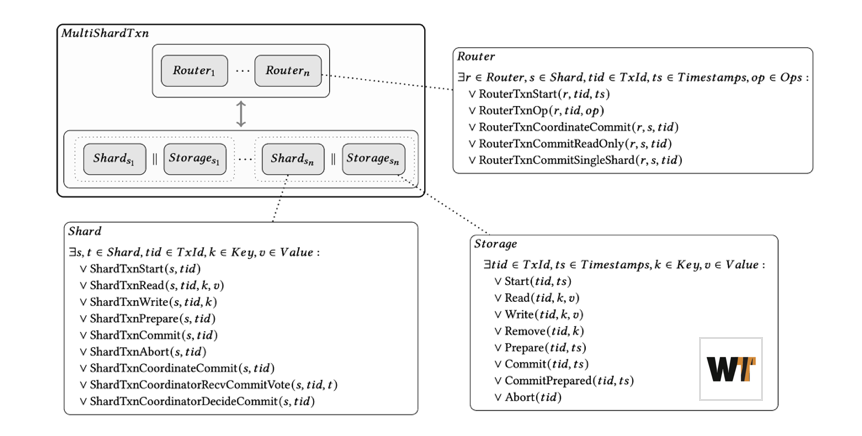

For a complex, layered system such as MongoDB, we wanted to establish a formal contract between the layers (for example, WiredTiger in particular) before we could compose a specification for the overall protocol. So, we developed a TLA+ specification of the protocol in a compositional manner, describing the high-level protocol behavior while also formalizing the boundary between the distributed aspect of the transactions protocol and the underlying single-node WiredTiger storage engine component. As mentioned above, the distributed transactions protocol can be viewed as running atop the lower-level storage layer.

Figure 4. Compositional specification of distributed transactions in TLA+.

Using this specification, we were able to validate isolation guarantees using a state-based checker based on the theory built by Crooks et al. (PODC ’17) and the TLA+ library implemented by Soethout. This library takes a set of committed transactions and their history of operations and checks whether the transactions satisfy snapshot isolation, read committed, etc.

Our specification also helps us formalize and analyze the guarantees provided by MongoDB transactions at different readConcern levels. As discussed in MongoDB documentation, “snapshot” readConcern provides standard snapshot isolation for transactions. At “local” readConcern, we provide a weaker isolation level, something more similar to a read-committed guarantee. Using the TLC model checker, we can check snapshot isolation and read committed isolation guarantees for these two readConcern levels with our TLA+ model in around 10 minutes and with around 12 cores for small instances of the problem. With just two transactions and two keys, the space is large but manageable, and bugs, if they exist, tend to show up even in small instances.

Permissiveness

Another benefit of our protocol specification extends beyond checking correctness, enabling us to measure a performance-related property we refer to as permissiveness. Essentially, for any transaction protocol implementing a given isolation level, we may care not only about its correct satisfaction of an isolation guarantee (safety) but also about whether it allows a suitable amount of concurrency. For example, a serializable transaction protocol will satisfy a snapshot isolation (or weaker) safety guarantee, but it’s probably not what we want if we are aiming for snapshot isolation as a guarantee (and its associated performance characteristics).

Moreover, even for a fixed isolation level, we might consider comparing how different protocol variants implement it, and whether one does a “better job” at allowing concurrency.

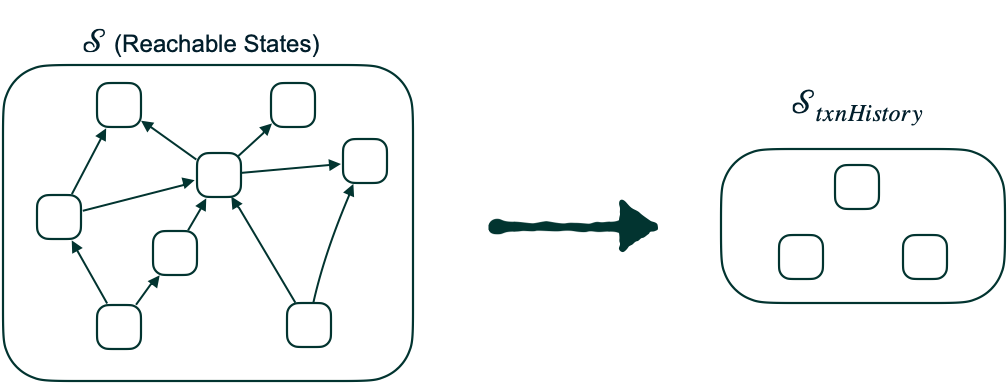

We can do this for finite state instances of a protocol by considering the full reachable state graph and projecting it down onto its transaction history variable (that is, the record of all committed transactions and their operation histories). We then compute the cardinality of this projected set as a ratio over the set of all transaction schedules allowed by the isolation definition. Similar notions of permissiveness have been treated in the world of transactional memory, but not directly in the context of distributed transactions protocols. This is a novel dimension of protocol analysis that demonstrates the value of formal methods beyond mere binary correctness outcomes.

Figure 5. Permissiveness metric definition.

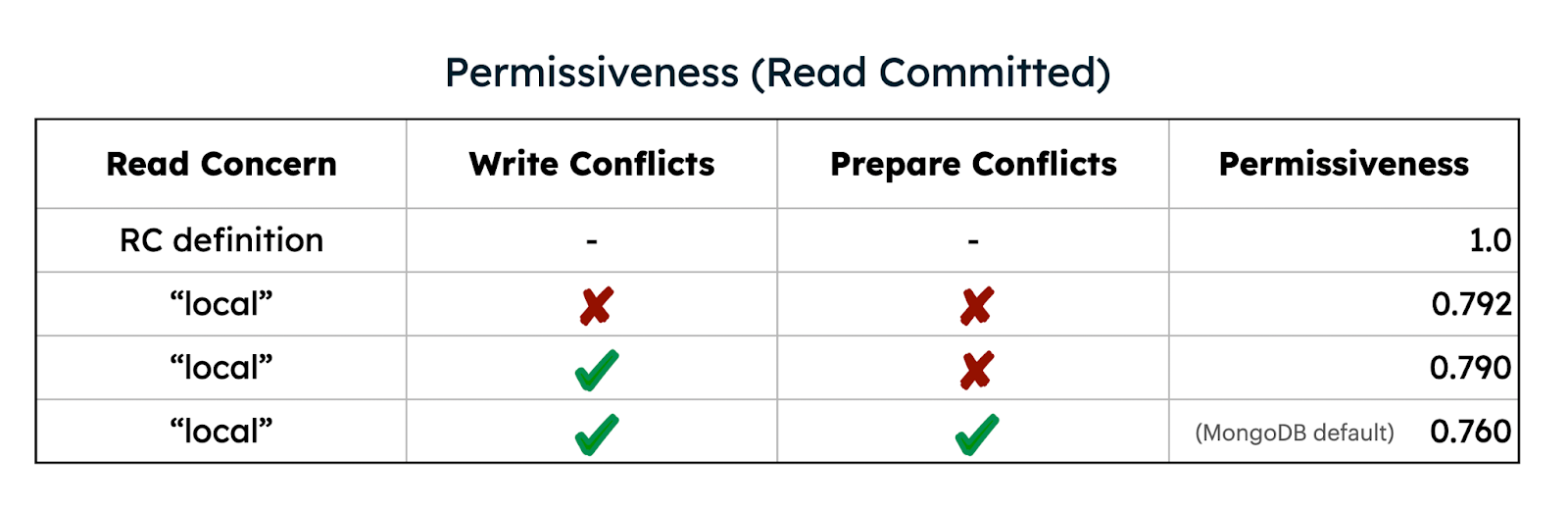

Computing this ratio for the protocol under various parameters enables us to quantitatively compare the restrictiveness of these different variations, and this process serves as guidance for potential isolation-level optimizations to increase concurrency.

For example, at MongoDB’s readConcern: “local” isolation level, we can compare its permissiveness level to a general read-committed definition, for finite protocol parameters. In particular, we can analyze permissiveness when weakening various storage engine concurrency control conditions, including prepare-conflict blocking (as discussed above) and/or write-conflict checking. Measuring permissiveness in these scenarios gives us a quantitative way to understand a protocol and guide it toward a theoretical optimal permissiveness level for a given isolation guarantee.

Figure 6. Permissiveness with different conflict behavior.

Conclusion

Modeling our transactions protocol demonstrated that this kind of approach enabled not only correctness verification but also performance-related analysis based on our permissiveness metric computation. The key takeaway for developers is assuredness: our approach gives stronger confidence that MongoDB’s distributed transactions behave correctly across layers, avoiding subtle correctness bugs that can be hard to detect in production. At the same time, by quantifying permissiveness, we can reason not just about safety but also about how much concurrency the protocol allows—directly impacting throughput and availability under load. This means developers can trust that their applications not only preserve ACID guarantees but also make efficient use of the system’s capacity, with fewer unnecessary aborts and retries.

In part two of this post, we will discuss how our compositional specification approach was instrumental in not only letting us reason about the abstract protocol correctness properties but also allowing us to automatically check that our abstract storage interface correctly matches the semantics of the implementation—that is, how we used our storage-layer specification for automatic model-based testing of the underlying WiredTiger key-value storage engine.

You can find more details about this work in our recently published VLDB ’25 paper and in the associated repo, which contains our specifications and code, as well as links to in-browser, explorable versions of our specifications. There has also been some interesting related work on verifying modern distributed transactions protocols, and past work on modeling distributed systems in a similar, compositional manner.